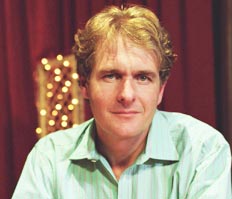

IN CONVERSATION WITH ROBERT BATHURST

|

It would be impossible to speak with Robert without discussing his portrayal of David Marsden in Cold Feet, a show which won the Golden Rose at the 1997 Montreux Festival to go alongside the bronze for Joking Apart. So it’s on this topic that we pick up in the concluding part of our interview.

--------------------------------------------------

JOKING APART.CO.UK: The pilot show was very self-contained, being primarily focussed on the characters of Adam and Rachel. Were you surprised when the series was commissioned and your role considerably expanded?

ROBERT BATHURST: The expansion sort of happened over a period of time. It was most certainly Adam and Rachel’s story and it was never sold to us as a series. I just thought it was a fifty minute comedy-drama that I was involved in – I didn’t see it as a runner. Certain people were saying, oh, this is definitely going to take off, and a lot of people were saying that it shouldn’t because it was just a rather good one-off and Mike Bullen had other ideas. As far as my part was concerned, if you read the description of the hapless David in the pilot, it’s very two-dimensional. The only character note was how much he earns a year. He was someone who earned a bit of money and was there to be booed at, really. I don’t think that that sort of character could sustain more than a brief cameo appearance and if you were going to develop into a series, he had to find some more flesh on the character; there had to be chinks of humanity to discover in this creature, and Mike Bullen succeeded in developing it.

I was really pleased when human complications were allowed to enter his behaviour and he wasn’t just a wholly predictable shit. In some ways, I’d have liked him to continue to be even shittier. That would have been nice. I started to feel sorry for him occasionally and that was all very well but I keep meeting people who are a hundred percent shits. There are people I’ve met whom you think, actually, would be written out of any comedy or any drama because they’d be unlikely characters but these people do exist. On the other hand, I enjoyed the fact that you started to have some sympathy for dear old David so I was very pleased that he did develop.

JA: David, of course, was such a different character to Mark Taylor – he wouldn’t have recognised a one-liner if it hit him in the face.

RB: No. David was, I think, a richly comic character without being remotely funny!

JA: Yes. Was it a relief to be cast against type?

RB: Against type? Both character-types are sardonic and not particularly appealing at times – they had unappealing traits about them. Both characters – neither of which I thought I was particularly qualified to do – I loved playing them. And I loved the way they developed. David was allowed to have his head a bit more and he also mixed with the Adam and Pete characters for a good reason, the reason being that their wives liked my wife….And there are these relationships you have with some dreadful character and you only tolerate him because you like her.

JA: Some members of the public seem to have this curious difficulty differentiating between acting and reality. Did you have anyone berate you because of some things that your character got up to?

RB: Depending on what he’d done in the series, over the five years, definitely. I had a fling in the series – I spent an afternoon in an hotel – and I had a few people say, “How could you do that to your wife? How could you possibly…? You know, it’s a terrible thing to do.” And I’d get knowing looks. Then the following year, David ended up crying on an aeroplane, coming back from Australia, and I got looks of great sympathy and people saying, “Oh, you poor thing!” So it worked both ways – sometimes pity and sometimes loathing.

JA: Amazing! I never quite understand how people don’t realise it’s just a TV show….

RB: The contract with a telly audience is different from stage, you know. In the theatre it’s no secret that it’s all make-believe. TV audiences can sometimes get more involved. Sometimes too much. It’s great that they do, in some ways, but you hope they have other lives.

JA: You’ve already spoken about the way David developed, but, for me, that was Mike Bullen’s stock in trade. Just when you think he’s taken things as far as he can go, he would find fresh ground.

RB: Yes, he did. He would plumb the depths of character, really, and work out what is unlikliest for someone to do, and make them do it. And he wouldn’t be too issue-based. There was the one where Adam had cancer. I’m sure he thought there was a danger of this show entering soap territory where we have to go through all the issues and -isms that there are in life and society and tick them off one by one but that didn’t seem to happen. It was more about characters and less about the issues, and because the characters were permitted to have human foibles and any sort of banner they carried saying that I represent this facet of humanity was sometimes ripped off, like human beings do, they did things which went against that.

JA: You just referred to Adam’s cancer episode. Now that is probably one of the abiding images of the series - the enormous testicles bouncing down the road after him

RB: I hated that sequence. I thought it was really unfunny. It was a lousy prop and awful graphics and there was too much of it – it would have been much better if it was like a Monty Python foot come smacking down like that and get it over with. You couldn’t keep up that surprise and hilarity for all the minutes it was on the screen.

JA: Being shot on film, it must have been a demanding schedule. How long would a typical series of Cold Feet take to shoot?

RB: Usually about five months, depending on how many episodes there were.

JA: You’re very much a family man so it must have been tough on you, being way for such long stretches….

RB: I enjoyed the work - it was good work. Away, yes, but at least not working in a submarine. I saw more of the family than a lot of people who are in the office five days a week. There were breaks, so I did manage to see them. The work was constant and it was great. I’ve spent a lot of time as an actor not doing work that’s particularly in the public eye and it’s fantastic when it arrives.

JA: Being involved in such a huge hit must have presumably changed your life considerably?

RB: It wasn’t a hit at the time; it became a hit. What was quite exciting was each series sort of took off. You know, it had the same rhythm to it. It could easily have gone the other way, but each series started with a bit of publicity and people going, “But is it going to be as good as last year?” and then you’d hear people talking about it and see people reviewing it and the figures would go up and, lo and behold, it was a hit. That happened five years running but each time had the same tension. So there was no guaranteed success - each season that came out was fraught with the possibility of ending up in daytime by the time we’d finished the series.

JA: Now presumably one of the legacies of the series must be that it’s given you more freedom over which scripts you accept and which ones you turn down.

RB: Yes, that’s right. I’ve just done a new series of My Dad’s the Prime Minister, which went out last year on a Sunday afternoon at six different times – again rotten scheduling – and Lorraine Heggessey [Controller of BBC One] is putting out the new series at 8.30 on a Friday night on BBC One, which is a prime time slot. It’s also been written and done more for adults – adults enjoyed the first series more than children. I have to say that the scripts for that, I think are really good, but some of the comedy that comes along that I do read is just dire. I’ve had the benefit of doing Steven Moffat’s stuff and Mike Bullen’s stuff and now Ian Hislop and Nick Newman’s series, which I think is up there, and it has meant that when the dire stuff comes through, I can try and filter it.

JA: I have to confess that’s not a series I saw anything of as I would always be working on a Sunday.

RB: It was ridiculous. Again, rather like our previous conversation about Joking Apart, we started at 6.30 and then, because of the war and the news always overrunning, then there was a Grand Prix and God knows whatever else going on, we ended up at 4.30 for the six episodes. Lorraine Heggessey was away and, apparently, the decisions were being made by someone called Damien in Scheduling, whom nobody knew and nobody could get hold of to discuss why. It got two million on a Sunday afternoon. It was warming people up for Songs of Praise – it wasn’t exactly the best slot!

JA: Certainly not! Now I’d like to ask you about another show that you starred in alongside Caroline Quentin in 2001 – a feature-length comedy-drama which was both funny and moving in turn, Goodbye Mr. Steadman. In that, you played a teacher who returns from an extended holiday to discover that he’s been officially declared dead, which has the most enormous and horrendous consequences for him. I remember thinking at the time that it seemed so frighteningly plausible.

RB: There was a Sandra Bullock film, which had a similar sort of plot and came out roughly at the same time we were making it – people might have thought it was a rip-off – but yes, sure. Whenever you punch in your details, they can be punched out again by somebody. There were credibility stretches – the time frame in which houses got sold and things got disposed of was, perhaps, a bit more rapid than would have happened in real life. But, if somebody hacks into your details, it is possible, I think, to delete someone, and officialdom is such that if you’re not on the record, you’re off it and you don’t exist. It was a frightful and emptying time for this character. It did, actually, also give him an opportunity for a renaissance – it gave him an ability to reinvent himself, and, of course, start his relationship with the Caroline Quentin character. She saw the goodness in him and drew him out in a way he hadn’t ever seen in himself….So it was a warm comedy – a “warmedy” as media types like to say.

JA: Yes, indeed. Earlier, you mentioned you’ve been doing My Dad’s the Prime Minister. What else have you been working on and what do you have in the pipeline?

RB: In January [2005], there’s an ITV two-part drama called The Stepfather, which I’ve just finished. What was great was I went straight onto that after My Dad’s the Prime Minister, which I think is funny, but this one has no jokes in it at all. It’s about a girl who goes missing. I’m her father and she lives with her stepfather and her mum – Philip Glenister and Lindsay Coulson. She goes missing and he blames me and I blame him and it all gets very unpleasant.

I’ve got no film credits, really, but I’m doing two films at the moment. One called The Thief Lord which I’m doing in Venice; and another one, a film of Heidi with Max von Sydow, Geraldine Chaplin and Diana Rigg which we’re doing in Slovenia and a studio outside of England.

JA: So hopefully more film work in the future?

RB: Yes. As I say, I haven’t done any movies, I’ve just had a decent telly career, so two film credits will be two more than I’ve had in the past few years.

JA: Which proves you’re going in the right direction….Thank-you very much, Robert, for kindly giving up your time for this interview and we look forward to seeing more of your work in the very near future.